|

| Ken Knowlton speaking at Arts Advocates meeting |

"It's a long story," Ken Knowlton began. Indeed it is. It's been more than 50 years since Knowlton and fellow Bell Labs engineer Leon Harmon created what is thought to be the first computer produced nude. It started as a prank.

Knowlton and Harmon decided to see if they could create a portrait of choreographer Deborah Hay by scanning her picture, keeping the outlines, and using numbers and symbols in place of the colors. (Needless to say, this is a wholly untechnical description of the groundbreaking process.) In addition to the challenge, they thought it would be funny to hang the 12' long image in their boss' office to surprise him when he came in the next morning. Their boss was not pleased. In his view, the image--now titled "Studies in Perception #1"-- was pornographic and had no place on the walls of the venerable Bell Labs. But that's not the end of the story.

|

"Studies in Perception #1" by Knowlton and Harmon (with an assist from Bell Labs) |

While Knowlton's boss wasn't enamored of the portrait, the art community was. To the dismay of the Bell Labs' PR department, the image began to get some press coverage. Knowlton and Harmon were told to keep Bell Labs' name out of it, thank you very much. Then "Studies in Perception #1" found its way into the

New York Times after Robert Rauschenberg heralded the portrait at a press conference held at his loft. Knowlton and Harmon asked that the image be attributed only to the two of them. Alas, Bell Labs got credit as well when it was published

. When "Studies in Perception #1" received a positive reception, Bell Labs decided it was art after all and was happy to be associated with the work. The lab's name was prominently listed thereafter, including when a smaller version of "Studies in Perception" appeared in an exhibit at MOMA entitled "The Machine as Seen at the End of the Mechanical Age."

|

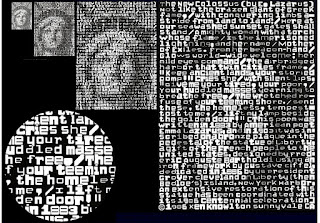

| Knowlton's "Statue of Liberty" |

Over time, Knowlton began to create his own pointillist portraits with his computer. Cleverly, many of his images use words and symbols related to the subjects. Helen Keller was captured using visual Braille; Samuel Morse out of Morse Code; and the Statue of Liberty from key phrases from the Statue of Liberty poem. (I'm sure you know the one about the United States taking in "the huddled masses yearning to breathe free.") In this picture, you can see how the image becomes more distinct the further away the viewer stands.

Knowlton eventually began to explore the use of other mediums (for lack of a better word) to create mosaic portraits. His trusty computer still plays an important role in his process.

|

| Tom Magliozzi (aka Click) by Ken Knowlton |

With a computer assist, he "draws" the contour lines of the image. The canvas is then placed on the floor and the work of creating the image with his objects begins. Mirrors are positioned above and to the side to enable Knowlton to determine the positioning of the pieces before gluing them onto the canvas.

In a nod to Magritte's painting "This is not a pipe," Knowlton used pieces of a teapot to devise his work "This is NOT not a Teapot." Two companion portraits portraying Click and Clack from the famed NPR radio show "Car Talk" were created using toy cars. His Julia Child emerges from an assortment of fruits and vegetables. The smaller the item used to create the work, the higher the difficulty of the puzzle.

Today, Knowlton uses seashells as his material. He does, after all, live in Florida. (In case you're wondering, he orders the seashells online rather than scouring our local beaches for them.)

|

"American Gothic (Version 2) after Grant Wood" by Ken Knowlton |

Initially, he arranged the shells in straight lines in the manner of his other portraits. But the curvature of the shells has enabled him to ratchet up the complexity of his creative process a notch. Now when he's in the thick of things he searches his bins for shells with both the desired reflectivity and shape. It's a labor of love -- and a far cry from the seashell art featured in the gift shops of the Panama City Beach of my youth.

Thanks to Arts Advocates for the introduction to the work of Ken Knowlton. For more information about Ken Knowlton, click

here. And to learn more about Arts Advocates and its programs, click

here.